The following is taken from Wikipedia

Black Mormons in early Mormonism

The initial mission of the church was to proselytize to everyone, regardless of race or servitude status.[5][6] When the church moved its headquarters to the slave state of Missouri, they began changing its policies. In 1833, the church stopped admitting free people of color into the Church for unknown reasons.[6]:13 In 1835, the official church policy stated that slaves would not be taught the gospel without their master's consent, and the following year was expanded to not preach to slaves at all until after their owners were converted.[6]:14 Some blacks joined the church before the restrictions, such as Joseph T. Ball and Peter Kerr, and others converted with their masters, including Elijah Abel, William McCary, and Walker Lewis.

The initial mission of the church was to proselytize to everyone, regardless of race or servitude status.[5][6] When the church moved its headquarters to the slave state of Missouri, they began changing its policies. In 1833, the church stopped admitting free people of color into the Church for unknown reasons.[6]:13 In 1835, the official church policy stated that slaves would not be taught the gospel without their master's consent, and the following year was expanded to not preach to slaves at all until after their owners were converted.[6]:14 Some blacks joined the church before the restrictions, such as Joseph T. Ball and Peter Kerr, and others converted with their masters, including Elijah Abel, William McCary, and Walker Lewis.

Jane Manning James had been born free and worked as a housekeeper in Joseph Smith's home.[7] When she requested the temple ordinances, John Taylor took her petition to the Quorum of the Twelve, but her request was denied. When Wilford Woodruff became president of the church, he compromised and allowed Manning to be sealed to the family of Smith as a servant. This was unsatisfying to Manning as it did not include the saving ordinance of the endowment, and she repeated her petitions. She died in 1908. Church president Joseph F. Smith honored her by speaking at her funeral.[8]

Other notable early black LDS Church members included Green Flake, the slave of John Flake, a convert to the church and from whom he got his name. He was baptized as a member of the LDS Church at age 16 in the Mississippi River, but remained a slave. Following the death of John Flake, in 1850 his widow gave Green Flake to the church as tithing.[9] Some members of the black side of the Flake family say that Brigham Young emancipated their ancestor in 1854, however at least one descendant states that Green was never freed.[10] Samuel D. Chambers was another early African American pioneer. He was baptized secretly at the age of thirteen when he was still a slave in Mississippi. He was unable to join the main body of the church and lost track of them until after the Civil War. He was thirty-eight when he had saved enough money to emigrate to Utah with his wife and son.[8]

Black Mormons in the United States[edit]

Before 1978, relatively few black people who joined the church retained active membership.[11] Those who did, often faced discrimination. LDS Church apostle Mark E. Petersen describes a black family that tried to join the LDS Church: "[some white church members] went to the Branch President, and said that either the [black] family must leave, or they would all leave. The Branch President ruled that [the black family] could not come to church meetings."[12] Discrimination also stemmed from church leadership. Under Heber J. Grant, the First Presidency sent a letter to then Stake President Ezra Benson in Washington D.C. advising that if two black Mormon women were "discreetly approached" they would be happy sit in the back or side so as not to upset some white women who had complained about sitting near them in relief society.[6]:43

On October 19, 1971, the Genesis Group was established as an auxiliary unit to the church. Its purpose was to serve the needs of black members, including activating members and welcoming converts. It continues to meet on the first Sunday of each month in Utah. Don Harwell is the current president.[13] When asked about racism in the church, he said "Now, is the church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints racist? No, never has been. But some of those people within the church have those tendencies. You have to separate the two."[14]

From 1985 to 2005, the church was well received among middle-class African-Americans, and African American membership grew from minuscule before 1978 to an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 in 2005.[15] A 2007 study by the Pew Research Center found that 3% of American Mormons were black.[16] African Americans accounted for 9% of all converts in the United States.[4] A 1998 survey by a Mormon and amateur sociologist, James W. Lucas, found that about 20 percent of Mormons in New York City were black.[17] Melvyn Hammarberg explained the growth: "There is a kind of changing face of the LDS Church because of its continuing commitment to work in the inner cities."[18] Sociology and Religious Studies Professor Armand Mauss says African Americans are particularly attracted by the focus on promoting healthy families. However, these numbers still only represent a fraction of total church membership in the United States, suggesting that African Americans remain comparatively hesitant to join, partly because of the church's past.[19] Still, Don Harwell, president of the Genesis Group, sees it as a sign that "People are getting past the stereotypes put on the church."[20]

LDS historian Wayne J. Embry interviewed several black LDS Church members in 1987 and reported that "all of the interviewees reported incidents of aloofness on the part of white members, a reluctance or a refusal to shake hands with them or sit by them, and racist comments made to them." Embry further reported that one black church member "was amazingly persistent in attending Mormon services for three years when, by her report, no one would speak to her." Embry reports that "she [the same black church member] had to write directly to the president of the LDS Church to find out how to be baptized" because none of her fellow church members would tell her.[21]:371

In the United States, researchers Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith, in their 2004 book Black and Mormon, wrote that since the 1980s "the number of African American Latter-day Saints does not appear to have grown significantly. Worse still, among those blacks who have joined, the average attrition rate appears to be extremely high." They cite a survey showing that the attrition rate among African American Mormons in two towns is estimated to be between 60 and 90 percent.[22]:7

In 2007, journalist and church member, Peggy Fletcher Stack, wrote, "Today, many black Mormons report subtle differences in the way they are treated, as if they are not full members but a separate group. A few even have been called 'the n-word' at church and in the hallowed halls of the temple. They look in vain at photos of Mormon general authorities, hoping to see their own faces reflected there.[23]

Growth in black membership

The church had an increase in membership upon repealing the ban by experiencing rapid growth in predominately black communities while other mainstream sects have been losing members.[20][48] After 1978 LDS Church growth in Brazil was "especially strong" among Afro-Brazilians, especially in cities such as Fortaleza and Recife along the northeast coast of the country.[49] By the 2010s, LDS Church growth was over 10% annually in Ghana, Ivory Coast, and some other countries in Africa. This was accompanied by some of the highest retention rates of converts anywhere in the church. At the same time, from 2009 to 2014, half of LDS converts in Europe were immigrants from Africa.[50] In the Ivory Coast LDS growth has gone from one family in 1984 to 40,000 people as of early 2017.[51][52] This growth lead to well over 30 congregations just in Abidjan by the early 2010s.[53] The revelation also helped pave the way for the church's exponential growth in areas like Africa and the Caribbean.[19] The church has been more successful among blacks outside the United States than inside, partly because there is less awareness of this past historic discrimination.[54] In 2005, the church had some 120,000 members in West Africa,[55] and the Aba Nigeria and Accra Ghana temples.

Regarding the LDS Church in Africa, professor Philip Jenkins noted in 2009 that LDS growth has been slower than that of other churches.[56]:2,12 He cited a variety of factors, including the fact that some European churches benefited from a long-standing colonial presence in Africa;[56]:19 the hesitance of the LDS church to expand missionary efforts into black Africa during the priesthood ban, resulting in "missions with white faces";[57]:19–20 the observation that the other churches largely made their original converts from native non-Christian populations, whereas Mormons often draw their converts from existing Christian communities.[56]:20–21 The church also has had special difficulties accommodating African cultural practices and worship styles, particularly polygamy, which has been renounced categorically by the LDS Church,[56]:21 but is still widely practiced in Africa.[58] Commenting that other denominations have largely abandoned trying to regulate the conduct of worship services in black African churches, Jenkins wrote that the LDS Church "is one of the very last churches of Western origin that still enforces Euro-American norms so strictly and that refuses to make any accommodation to local customs."[56]:23

Notable black Mormons[edit]

- Ezekiel Ansah, Ghanaian-born football player.

- Thurl Bailey, basketball player and singer.

- Alex Boyé - actor and musician.[65]

- Alan Cherry, Latter-day Saint singer and actor.

- Eldridge Cleaver, former Black Panther Party leader.

- Edward Dube, member of the First Quorum of the Seventy.

- Alvin B. Jackson, Utah State Senator

- Frank Jackson, basketball player

- Jane Manning James, one of the first black members of the church

- Ebenezer Joshua, first Prime Minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

- Gladys Knight, who joined the church in 1997, created and now directs the LDS choir Saints Unified Voices.[66]

- Emmanuel A. Kissi, Ghanaian medical doctor and writer.

- Mia Love, former mayor of Saratoga Springs, Utah and member of the United States House of Representatives.

- Marcus Martins, sociologist

- Julia Mavimbela, school teacher and community leader in South Africa

- Burgess Owens, football player and writer.

- Jabari Parker, basketball player

- Niankoro Yeah Samake, presidential candidate in the country of Mali.[67]

- Joseph W. Sitati, member of the First Quorum of the Seventy.

- Catherine Stokes, former deputy director of the Illinois Department of Public Health, in August 2010 she was one of the original 13 members of the Deseret News Editorial Advisory Council.[68]

- Winston Wilkinson, American politician.

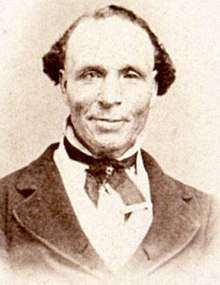

Elijah Abel

| Elijah Abel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Third Quorum of the Seventy | |

| December 20, 1836 – December 25, 1884 | |

| Called by | Joseph Smith |

| Elder | |

| January 25, 1836 – December 20, 1836 | |

| Called by | Joseph Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 25, 1808 Frederick-Town, Maryland |

| Died | December 25, 1884 (aged 76) Salt Lake City, Utah Territory |

| Resting place | Salt Lake City Cemetery 40°46′37.92″N 111°51′28.8″W |

Elijah Abel, or Able[1] (July 25, 1808 – December 25, 1884)[2] was one of the earliest African-American members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He is considered by many to have been the first African-American elder and seventy in the Latter Day Saint movement.[3] Abel, although predominantly of Scotch and English descent,[4] appears by his African heritage to have been the first and one of the few black members in the early history of the church to have received the priesthood.[3][5] And it was his distinction to be the faith's first missionary to have descended in part through African bloodline.[3] But in 1849, Brigham Young declared all African-Americans ineligible to hold the priesthood and Abel's claim to priesthood right was also challenged. As a skilled carpenter, Abel often committed his services to the furthering of the work and to the building of LDS temples. He died in 1884, shortly after serving a final mission for the church (in his lifetime he officially served three) to Cincinnati, Ohio.[6][7]

No comments:

Post a Comment