World War I and Utah

Allan Kent Powell

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

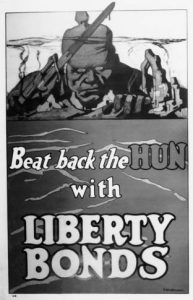

WORLD WAR I POSTER ENCOURAGING THE PURCHASING OF LIBERTY BONDS

Known as “The Great War” until the outbreak of World War II, World War I began on 1 August 1914 and ended with armistice on 11 November 1918. The two warring sides were the Allies—comprised of Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy, United States, Japan, Romania, Belgium, Serbia, Greece, Portugal, and Montenegro; and the Central Powers which included Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria. During the course of the war, Utahns were affected by the events in many ways. Immigrants followed events in their warring homelands, sent aid, volunteered to return to fight, and encouraged other Utahns to sympathize with the side they favored. Utah’s economy prospered because of the war. New coal mines were opened, metal and copper mining expanded, smelters ran at or near full capacity, and farmers and ranchers received more for their crops and animals than any other time in recent decades.

After the United States entered the war on 6 April 1917, many Utahns were directly affected as relatives and friends joined the armed services or were drafted. Approximately 21,000 Utahns saw military service; of these, 665 died and 864 were wounded. Of the 665 deaths, 219 were killed on the battlefield or died from wounds received in action; 32 died of accidental causes; the remaining 414 died from disease and illness. Approximately 10 percent (2,156) of the Utahns who served were of foreign birth or were members of U. S. ethnic or racial minorities. A number of Utah women, including eighty registered nurses, served during the war as nurses, ambulance drivers, and clerical and canteen workers.

In the summer of 1914, most Utahns were little concerned with the rumblings of war in Europe. Most felt that the fight had little to do with United States interests, advocated a strict policy of neutrality, and insisted that the United States not become embroiled in a European conflict. There were exceptions, of course, primarily among the Utah immigrant groups including the South Slavs, Germans, Greeks, and Italians whose homelands had been caught up in the Great War. Utah German-Americans openly demonstrated their sympathy for Germany, held rallies, collected money for the German Red Cross, complained of the virulent anti-German propaganda in most English-language newspapers, and, in some cases returned to Germany to fight.

As the war continued, America’s position as a neutral became continually more difficult, especially with the loss of 124 American lives when the passenger ship Lusitania was sunk off the coast of Ireland in May 1915. After the outcry against Germany over the sinking of the Lusitania, Germany complied with American demands that ships carrying neutral passengers and cargo be allowed to sail without attack. By 1917, German strategists concluded that their best hope for victory was to resume unrestricted submarine warfare to keep essential war material from reaching the French and English, launch an offensive along the Western Front designed to end the nearly three years of stalemate, and to seek a secret alliance with Mexico which would restore to that nation the territory (including Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and California) lost to the United States in 1848. Faced with these events, President Woodrow Wilson saw no other option than to ask Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, which was passed on 6 April 1917.

Even before war was officially declared, Governor Simon Bamberger issued a proclamation on 24 March 1917 calling for Utahns to enlist in the Utah National Guard. Four months after war was declared, the Utah National Guard was drafted into Federal Service on 5 August 1917, sent to California, and then on to Europe where Utahns saw action along in the Argonne Forest, and at Chateau Thierry, Champagne, Soissons, St. Mihiel, Verdun, and other locations on the Western Front.

World War I helped bring Utah into the mainstream of American life as much as anything during the first two decades of the twentieth century. As part of the national war effort, Utahns planted “victory gardens,” preserved food, volunteered for work in the beet fields and on Utah’s fruit farms, purchased Liberty Bonds, gave “Four Minute” patriotic speeches, collected money for the Red Cross, used meat and sugar substitutes, observed meatless days, knitted socks, afghans, and shoulder wraps, wove rugs for soldiers’ hospitals, made posters, prohibited the teaching of the German language in some schools, and cultivated patriotism at every opportunity.

Utah’s economy prospered as wartime demands for farm and orchard produce, sugar, beef, coal, and copper placed a demand on production far beyond peacetime conditions.

Fort Douglas was an important military facility during the War. Thousands of recruits were trained at the fort and a prison was set up at the fort to house 870 enemy aliens, who had expressed pro-German sentiments or were considered dangerous, and as well as draft resisters from all states west of the Mississippi. An adjacent but separate part of the prison housed 686 German naval prisoners of war, who were sent to Utah after their ships were seized by American forces in Guam and Hawaii.

VETERANS’ PARADE IN OGDEN, 1919

Most Utah servicemen returned home early in 1919 to cheering crowds, impressive parades, enthusiastic celebrations, and generous parties even though the influenza epidemic necessitated some precautions. Many joined the American Legion as posts were established in most Utah cities and towns. They were honored when the nation proclaimed 11 November as Armistice Day, a national holiday, and were moved when “Memory Grove,” located along City Creek at the mouth of City Creek Canyon just north of the downtown Salt Lake City, was dedicated on 27 June 1924, as a permanent memorial to the soldiers killed during the war.

Like many other Americans, Utahns became disillusioned with the formal peace treaty ending the war. They were also divided over Woodrow Wilson’s primary objective, the establishment of the League of Nations. Heber J. Grant, who became President of the LDS church in 1918, was an advocate of the League of Nations while Reed Smoot, an LDS apostle and Utah’s senior senator in Washington D. C. was an outspoken critic of the League. The war was something that many seemed to never really understand, a situation that hampered international cooperation and understanding and led to increased tensions and another war within a generation.

See: “Utah and World War I,” Utah Historical Quarterly, (fall 1990); and Noble Warrum, Utah in the World War (1924). John Sillito, “Drawing the Sword Against the War: B.H. Roberts, World War I, and the Quest For Peace,” Utah Historical Quarterly 87, no. 2, 2019, Tammy M. Proctor, “The Great War and The Making of a Modern World,” Utah Historical Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2018), Allan Kent Powell, “Utah and World War I,” Utah Historical Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2018), Robert S. Means, “Try To Be As Brave Cross-Continental Comparisons of Great War Poetry,” Utah Historical Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2018),

Allan Kent Powell

Utah History Encyclopedia, 1994

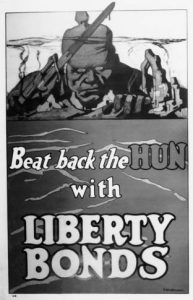

WORLD WAR I POSTER ENCOURAGING THE PURCHASING OF LIBERTY BONDS

Known as “The Great War” until the outbreak of World War II, World War I began on 1 August 1914 and ended with armistice on 11 November 1918. The two warring sides were the Allies—comprised of Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy, United States, Japan, Romania, Belgium, Serbia, Greece, Portugal, and Montenegro; and the Central Powers which included Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria. During the course of the war, Utahns were affected by the events in many ways. Immigrants followed events in their warring homelands, sent aid, volunteered to return to fight, and encouraged other Utahns to sympathize with the side they favored. Utah’s economy prospered because of the war. New coal mines were opened, metal and copper mining expanded, smelters ran at or near full capacity, and farmers and ranchers received more for their crops and animals than any other time in recent decades.

After the United States entered the war on 6 April 1917, many Utahns were directly affected as relatives and friends joined the armed services or were drafted. Approximately 21,000 Utahns saw military service; of these, 665 died and 864 were wounded. Of the 665 deaths, 219 were killed on the battlefield or died from wounds received in action; 32 died of accidental causes; the remaining 414 died from disease and illness. Approximately 10 percent (2,156) of the Utahns who served were of foreign birth or were members of U. S. ethnic or racial minorities. A number of Utah women, including eighty registered nurses, served during the war as nurses, ambulance drivers, and clerical and canteen workers.

In the summer of 1914, most Utahns were little concerned with the rumblings of war in Europe. Most felt that the fight had little to do with United States interests, advocated a strict policy of neutrality, and insisted that the United States not become embroiled in a European conflict. There were exceptions, of course, primarily among the Utah immigrant groups including the South Slavs, Germans, Greeks, and Italians whose homelands had been caught up in the Great War. Utah German-Americans openly demonstrated their sympathy for Germany, held rallies, collected money for the German Red Cross, complained of the virulent anti-German propaganda in most English-language newspapers, and, in some cases returned to Germany to fight.

As the war continued, America’s position as a neutral became continually more difficult, especially with the loss of 124 American lives when the passenger ship Lusitania was sunk off the coast of Ireland in May 1915. After the outcry against Germany over the sinking of the Lusitania, Germany complied with American demands that ships carrying neutral passengers and cargo be allowed to sail without attack. By 1917, German strategists concluded that their best hope for victory was to resume unrestricted submarine warfare to keep essential war material from reaching the French and English, launch an offensive along the Western Front designed to end the nearly three years of stalemate, and to seek a secret alliance with Mexico which would restore to that nation the territory (including Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and California) lost to the United States in 1848. Faced with these events, President Woodrow Wilson saw no other option than to ask Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, which was passed on 6 April 1917.

Even before war was officially declared, Governor Simon Bamberger issued a proclamation on 24 March 1917 calling for Utahns to enlist in the Utah National Guard. Four months after war was declared, the Utah National Guard was drafted into Federal Service on 5 August 1917, sent to California, and then on to Europe where Utahns saw action along in the Argonne Forest, and at Chateau Thierry, Champagne, Soissons, St. Mihiel, Verdun, and other locations on the Western Front.

World War I helped bring Utah into the mainstream of American life as much as anything during the first two decades of the twentieth century. As part of the national war effort, Utahns planted “victory gardens,” preserved food, volunteered for work in the beet fields and on Utah’s fruit farms, purchased Liberty Bonds, gave “Four Minute” patriotic speeches, collected money for the Red Cross, used meat and sugar substitutes, observed meatless days, knitted socks, afghans, and shoulder wraps, wove rugs for soldiers’ hospitals, made posters, prohibited the teaching of the German language in some schools, and cultivated patriotism at every opportunity.

Utah’s economy prospered as wartime demands for farm and orchard produce, sugar, beef, coal, and copper placed a demand on production far beyond peacetime conditions.

Fort Douglas was an important military facility during the War. Thousands of recruits were trained at the fort and a prison was set up at the fort to house 870 enemy aliens, who had expressed pro-German sentiments or were considered dangerous, and as well as draft resisters from all states west of the Mississippi. An adjacent but separate part of the prison housed 686 German naval prisoners of war, who were sent to Utah after their ships were seized by American forces in Guam and Hawaii.

VETERANS’ PARADE IN OGDEN, 1919

Most Utah servicemen returned home early in 1919 to cheering crowds, impressive parades, enthusiastic celebrations, and generous parties even though the influenza epidemic necessitated some precautions. Many joined the American Legion as posts were established in most Utah cities and towns. They were honored when the nation proclaimed 11 November as Armistice Day, a national holiday, and were moved when “Memory Grove,” located along City Creek at the mouth of City Creek Canyon just north of the downtown Salt Lake City, was dedicated on 27 June 1924, as a permanent memorial to the soldiers killed during the war.

Like many other Americans, Utahns became disillusioned with the formal peace treaty ending the war. They were also divided over Woodrow Wilson’s primary objective, the establishment of the League of Nations. Heber J. Grant, who became President of the LDS church in 1918, was an advocate of the League of Nations while Reed Smoot, an LDS apostle and Utah’s senior senator in Washington D. C. was an outspoken critic of the League. The war was something that many seemed to never really understand, a situation that hampered international cooperation and understanding and led to increased tensions and another war within a generation.

See: “Utah and World War I,” Utah Historical Quarterly, (fall 1990); and Noble Warrum, Utah in the World War (1924). John Sillito, “Drawing the Sword Against the War: B.H. Roberts, World War I, and the Quest For Peace,” Utah Historical Quarterly 87, no. 2, 2019, Tammy M. Proctor, “The Great War and The Making of a Modern World,” Utah Historical Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2018), Allan Kent Powell, “Utah and World War I,” Utah Historical Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2018), Robert S. Means, “Try To Be As Brave Cross-Continental Comparisons of Great War Poetry,” Utah Historical Quarterly 86, no. 3 (2018),

No comments:

Post a Comment